The transaction was carried out in the stillness of the night, where the only spotlight on the furtive affair came from the brightness of the full moon. It was on that night that my adopted mother decided to name me after the moon goddess, Hắng Nga. The goddess protected us in her warmth, and she protected me in her gaze. I stare up at the moon during Tết Trung Thu, or the mid-autumn festival, every year since the discovery of my adoption. I think about how they must have felt when they gave me up. I think about the tears that must have singed my birth mother’s face. And I think about what it must mean to want to protect our children.

I haven’t celebrated tết traditionally in nearly twenty-years; this year, I was able to celebrate it for the first time in Vietnam. The festival occurs during the fifteenth day of the eighth lunar months of the Lunar calendar (usually somewhere in mid-September) and is truly considered a festival for the children. The tradition began as a way for parents to make up for lost time with their children due to long hours during harvest season. Dark streets become ablaze with colorfully lit lanterns, and the once murky river is now covered in a veil of twinkling lights.

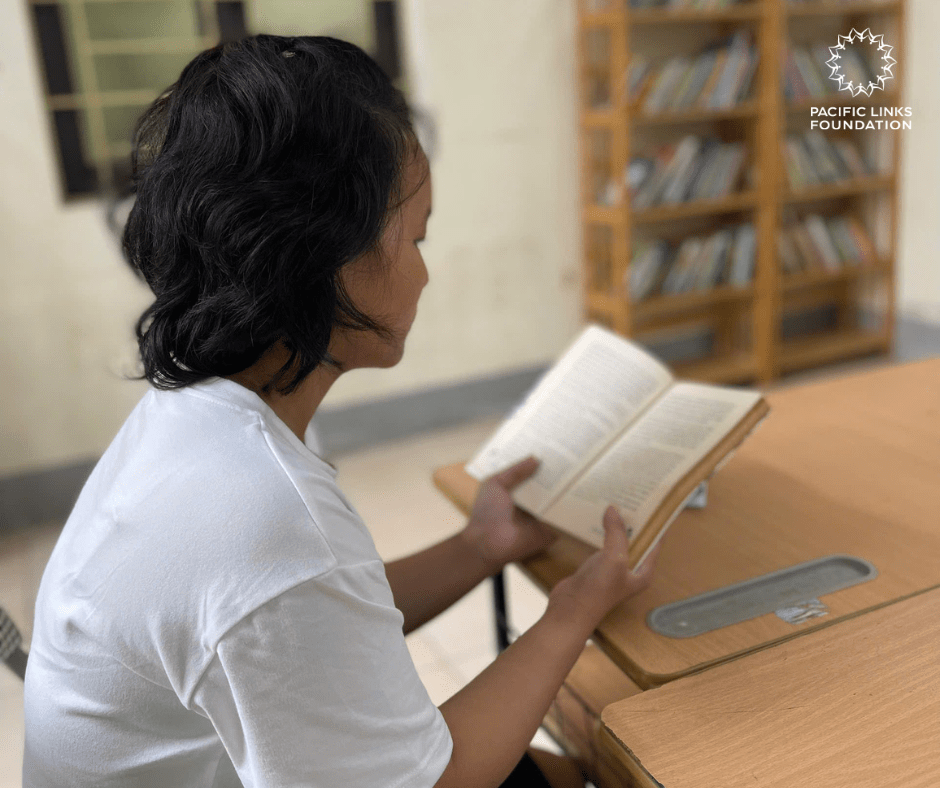

This has also been my first couple of weeks with Pacific Links Foundation. I have been working with the girls at our reintegration shelter in Long Xuyen all week long to prepare for the Moon Festival. But really, what that means is that I sat and watched their handicraft with amazement. The girls cut and shave large bamboo poles down to a more pliable material, and then the sticks are configured into a 3D shape of their choosing (usually a star or a cylinder). It’s rare nowadays for people to make these lanterns by hand since they can be easily picked up around the corner for less than a dollar. But besides the perennial challenge of working on a small budget, what we try to instill in these girls at every turn is a sense of ingenuity and resourcefulness. The ultimate goal is to foster their ability to survive without the organization and the mentors. In a sense, they must learn to become as pliable as the lantern’s infrastructure. This week, I learn that this is what protecting our children meant.

It has been estimated by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) that one in five victims of human trafficking are children, and in poorer regions like the Mekong delta where we work, that number is much higher. While trafficking for sexual exploitation has gained traction in the public consciousness, other forms of trafficking such as forced labor, debt bondage, involuntary domestic servitude, and forced organ removal are less well known. Trafficking victims are often lured by the people they know –acquaintances, friends, lovers, and even family – and are recruited through deception and false promises of a more worthwhile life. What are the consequences of this treacherous recruiting tactic? How will the deceit from a kin pull at the fibers of our community? – Because everyone here is a relative. Everyone is your uncle (chú), your aunt (cô), your sister (chị) and your brother (anh). Our relationship to others is encapsulated within our language; and therein lies the root of our trust.

We don’t have the luxury of treating these girls like children. We have to think twice or three times before we do something as simple as buy them a treat or a toy to play with. We have to think about the message behind all of our words and actions. As much as I would like to sit beside them as a friend—as a sister—and treat them to all the delicacies that I think they are entitled to as a child, I must first keep in mind our program’s objective of cultivating self-reliance. The reintegration process must also, therefore, address the vulnerability of victims to further exploitation. Our role is to provide a safe and enabling environment for recovery and development. But our success will ultimately be defined in their capacity to care for themselves and to make the right decisions.

Hang Tran