In the United States, a bag of name-brand coffee will cost about $12. In Ho Chi Minh City, it costs 35,000 Dong ($1.75 USD) to order a Vietnamese iced coffee in an air-conditioned upscale café, or 10,000 Dong (50 cents) to have your coffee in a disposable cup instead of from a vendor in the park.

Here, in this urban chaos of business and motorbikes, you will sometimes meet someone, either a foreigner or Vietnamese, and he will ask you what you do. In response to your saying that you work on anti-trafficking along the borders of Vietnam, he will say knowingly, “Yes, I hear so many of these poor parents sell their own children for a few dollars, or a bag of coffee or something.”

You will respond with, “Actually, from our experiences with trafficking returnees, the girls are most often tricked by acquaintances of the family, or perhaps even a relative, usually because the girls were looking for a job. The parents often don’t have enough money to send their children to school, so their children will often quit school early and try to find work to help out, which leaves them vulnerable to being tricked and sold.”

Usually, this person will nod absent-mindedly, look away, and then change the topic.

What you don’t get to say is, “What kind of parent do you think being poor makes you?”

It costs 150,000 Dong ($7.50) one-way for a seat in an 18-person van that will end up crowding in 24 people for a 9-hour bumpy ride from Ho Chi Minh to Kien Giang. On that ride, the window won’t be able to close, the door will jam and no longer open, the man perched on the child’s plastic chair next to you will keep falling asleep on your shoulder, so that you have to push him off at the same time that you are slapping the mosquitoes from your feet, and someone behind you will become carsick several times during the trip. But once you step out of the van, the landscape stretches out around you in bright shocks of green rice paddies, trees of ripening papaya, tangled dragon fruit branches, and everywhere, the presence of water, in the brown rivers of the Mekong and the still, clear pools of farmed shrimp.

In this borderland province, for a family of 4, where the mother and father have hired hands, renting themselves out for work in other people’s fields and attempting the risky business of raising shrimp (risky, because a shrimp virus can wipe out an entire season’s earnings, as well as poison the pond for several successive seasons), they will take home about 150,000 Dong ($7.50) a month, or 5000 Dong (25 cents) a day, after their land rent is deducted. Whatever they can plant and forage for around their house, built from dirt and water-palm leaves, is what they will eat. They will occasionally splurge to buy ice.

For their two daughters to attend school, they must consider how to pay for the school fees, facility expenses (such as building maintenance), uniforms, textbooks, and school supplies on 25 cents a day. They also must factor in the loss of income if they allow their children to continue their education instead of having them sell lottery tickets or help in the fields. They must weigh their daughters’ tearful pleadings to attend school, and their quiet, desperate love for their children, desperate beyond the short-term logic of their finances. They must balance what school means as an investment in their children’s future, decades in the distance when they are sometimes uncertain what the next few months will look like from the shallow bottom of a rice bowl.

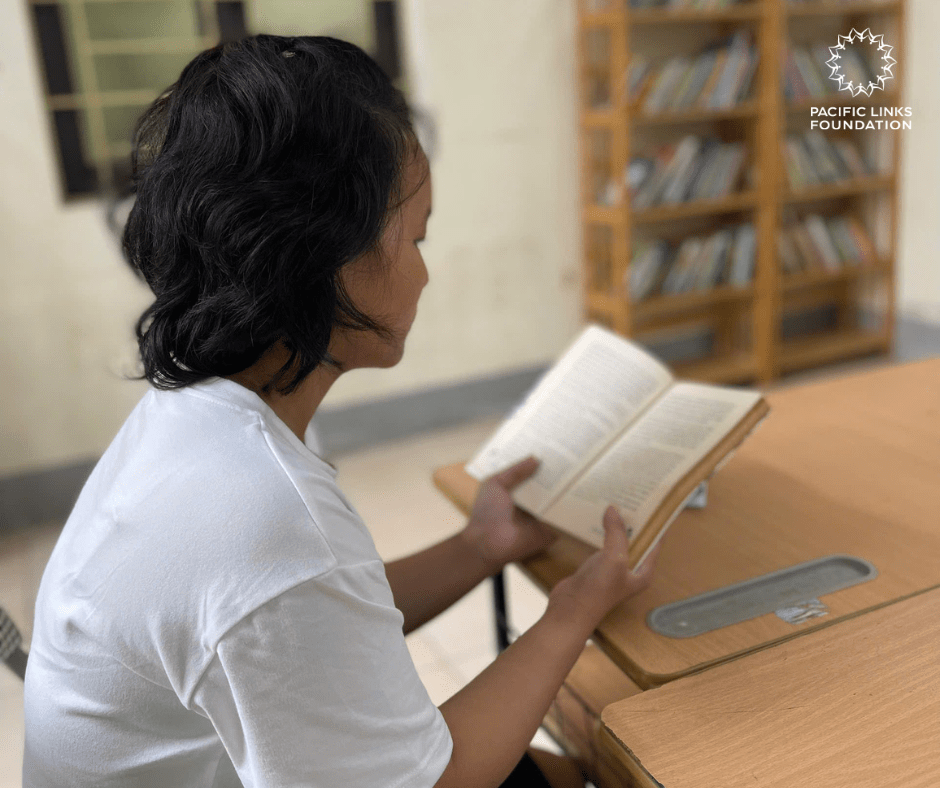

You ask her, “If our program runs out of money, and we can no longer provide a scholarship for you to attend school, do you think your parents will try to help you finish 12th grade?” She is in 8th grade and wants to be a doctor. She cries when she says this. She shares a bicycle with her 11-year old sister, biking to school for her morning session classes, and then coming home at noon so that her sister can take the bicycle to attend her afternoon session. Between the two of them, they also share 22 certificates of achievements that they can’t hang up on their walls, for fear that the rains that pour through the gaps in the water-palm leaves will ruin the papers. She answers, “Yes, if my parents are able to.”

“And what if they’re not able to?”

She looks at you, wanting to answer, wanting to please you, but nothing comes out, and tears well up in her eyes. She puts her head down and whispers, “I don’t know.”

There is a child’s love that can sound like honor and duty, that can look like quitting school and working with fingertips black from picking peppers for several cents a kilogram, that can feel like a letting go of dreams that can’t be dreamed, that can taste like a tender, bittersweet pain.

There is a parent’s love that can sound like sacrifice and responsibility, that can look like bent-over fieldwork from before sunrise to after sunset, skin dark and calloused, this caring for one’s children that can feel like a burden of lightness, a deep, unspoken longing for them to have a life that is better, gentler than your own, this painful sorrow so sharp it can taste like hope.

Along the roads back from Kien Giang, passing next to rows of farmed shrimp pools, you can see, reflected in the still waters, the deepening blue of the sky. Above and below you, there is nothing but sky.

Pacific Links Foundation scholarships cost $200 for one student’s educational expenses for a year. We currently provide scholarships for 384 at-risk girls annually, with the goal of providing scholarships to 1000 girls annually by 2014. You can help by sponsoring one or multiple scholarships to enable at-risk girls to continue attending school.

Nhu Tien Lu