For the past three weeks, I’ve been living and working at Pacific Links Foundation’s reintegration shelter for trafficking survivors in northern Vietnam. There are twelve girls, ages thirteen to twenty-two, from five different minority ethnicities, currently residing there. When I boarded the flight back to Saigon, my legs were scarred with flea bites from the rural visits, my bags were heavy with miniature pineapples and northern plums, and I was weighted with stories, these girls’ stories whose wings I can feel urgently fluttering against my ribcage, trying to find their way out.

A path through stone corn to her house.

In northern Vietnam, about an hour’s drive from Lao Cai and a steep fifteen-minute walk along dense rows of stone corn and narrow ledges of rice paddies live a Hmong girl. She is thirteen, which is old enough to have worked in the fields since her first memory, old enough to be snatched off for marriage, old enough to be sold with her mother and two sisters to China.

There are details about those four months spent in China that she will have to relive and retell over and over. These are the answers that she will have to recount to the police, the immigration officials, the social workers, the researchers, and to story seekers like myself.

I was born in the year of the mouse.

In my family, I have my mom and dad, two sisters and two brothers, and a nephew we’re caring for since his mother was sold last year to China.

My uncle invited my mom and sisters on a holiday and he promised to pay for everything. So we went with him by car, and then by boat, and then again by car once we arrived in China.

I knew that we had been sold when my uncle took the money and the two men who had taken us by boat said that we could no longer go home.

I lived with my mom and younger sister for two months, then I was sold for 12,000 yuan ($856 USD) to become the wife to a thirty-year-old man. The family cursed at me frequently in Chinese, but I could understand, even if I didn’t know all the words. They tried to force me to learn Chinese, but I would resist; I would purposefully not listen or pay attention. They told me that they couldn’t afford to pay for a wedding with a Chinese woman for their son, so they bought a Vietnamese girl instead. I went to work with them in the fields and did housework. My older sister lived nearby since she had been sold to another man in the same neighborhood, and we would call each other as often as we could and cry together.

After four months there, I escaped with my older sister and we hired a taxi to take us to the police station, lying to the driver that we had to fill out some paperwork there because we were afraid he would bring us back to our husbands if he knew we were running away. We spent a total of two days at the border police station, two weeks at the Vietnam migration shelter, and then we were home for 4 days before we arrived at the Pacific Links reintegration shelter.

Then there are the details that she is not asked about, those memories that don’t make it into the notebooks of policemen or policy research interviewers.

I have fond memories of New Year’s day when my dad would celebrate by buying a few cans of soda to place on the altar, and after the spirits had drunk, we could bring them down and drink them.

She washes chopsticks in preparation for lunch during our visit, her white plastic shoes in the background.

She washes chopsticks in preparation for lunch during our visit, her white plastic shoes in the background.My parents bought my first pair of shoes for school, little plastic ones that cost 5000 Dong (25 cents US) and I’d walk barefoot to school, then put the shoes on, and then after school, I’d walk back home barefoot. I was so afraid of wearing down those shoes.

I had a baby chick when I was young, but one day it was hopping around the house, crying -chirp chirp chirp- and my sister, who was sweeping the dirt floor, became irritated at the noise, and so she brushed it out into the field and it died. It was so small. I cried and cried.

When I was supposed to be tending to the water buffalos after school, if my parents weren’t around, I would shape the damp red earth into figurines, and pretend that my clay was a princess who lived in a castle, and I could do this for hours -meanwhile having to slap away the fleas that landed thick and dark on my legs- and if my sisters were with me, then my princess could go visit their princess in their castle.

In China, the family would turn off the television at 11 pm, and I would go upstairs to my bed and sit there, awake, still, until 3 or 4 in the morning. I would think about how to escape. I would think about killing myself. Sometimes I just thought. I would ask my sister, when life and death are the same misery, then what’s the difference? But I once overheard the family talking about a dumb girl who escaped back to Vietnam, and I thought if she’s a stupid girl and she managed to run away, then how ridiculous would it be if I couldn’t? And after that, I stopped thinking about suicide and only thought of how to escape.

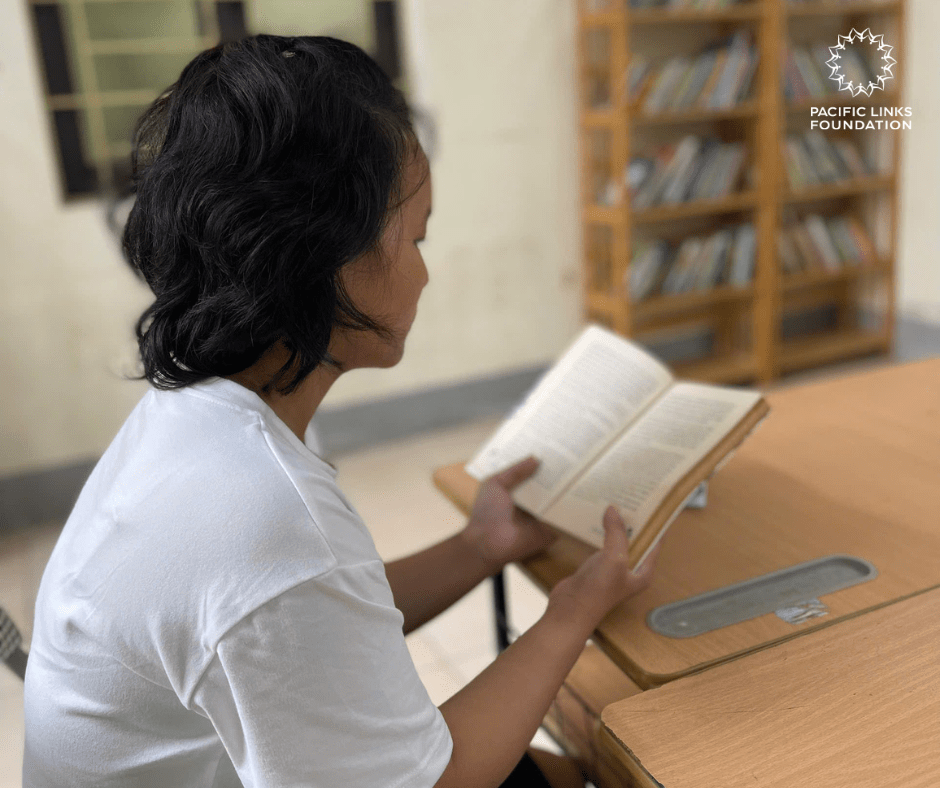

She is now planning on finishing her schooling while at the shelter. When asked what she wants to study, she says, anything. Everything. She is so clever that you believe her, you think everything is truly possible for her if she should want it. Her laughter is open, wide, infectiously bright, so deep that you can’t imagine her sadness.

She says: “I dream of one day owning a house with two stories. Of having a lot of money so I can buy whatever I want. Of going swimming in the ocean.”

Anything else?

She looks down, and then she says, softly: “I dream that one day I’ll forget.”

And then she begins to cry, this vibrant, shining girl who has, for the first time since you’ve met her, stopped smiling. You wrap her in a hug and you hold her for several minutes while she cries, although you can’t tell who’s crying harder.

And in a while, she’ll dry her eyes and you’ll say something to make her smile, and when she does, her wide, deep laugh bright as a morning in the room, you’ll see how her laughter is fierce with courage and resistance and light.

But for now, you let her cry, her thin shoulders against your arms.

There is a thirteen-year-old Hmong girl you now know, and whose story you will tell to others, who laughs all the time, who cried over baby chicks and refused to learn Chinese, and who dreams of one-day forgetting.

Nhu Tien Lu